Troop 1 - Mendham, New Jersey

- Home

- Troop

- Trips and Events

- Calendar

-

Pictures

- Backpacking

- High Adventure >

- Winnebago Scout Reservation

- West Point Camporee 2018

- Statue of Liberty 2024

- Skiing >

- Sabattis

- Scuba Certification

- Camp Somers

- Canoeing

- Caving

- Climbing

- Court of Honor

- Gettysburg

- NJ State Police Camporee

- Ricketts Glen

- Shooting Trip

- Deep Sea Fishing

- Klondike Derby

- National Jamboree

- Revolutionary War Outing

- Troop Meetings >

- Annapolis Trip

- Rafting Trip

- Forms

- Useful Links

- Contact Us

-

Archive

- AT Hike - Spring 2024

- AT Hike - Fall 2023

- High Adventure 2023 (Pyrenees)

- AT Hike - Fall 2022

- AT Hike - Spring 2022

- Sea Base 2022 v2

- Sea Base 2022

- Summer Camp - 2022

- AT Hike - Fall 2021

- AT Hike - Spring 2021

- Scuba Discovery Feb 2021

- LM-JH Day Hike

- Klondike Derby - Jan 2021

- Webelos Woods - Fall 2020

- Bike Trip October 2020

- AT Hike - Fall 2020

- Pumpkin Sale Fall 2020

- Philmont 2021

- Philmont Questionnaire 2020

- Shooting Trip - Fall 2020

- AOL Crossover Ceremony - July 2020

- Sabattis 2020

- Scuba Discovery Mar 2020

- NJ State Police Camporee - May 2020

- Annapolis March 2020

- Homeless Solutions_Jan2020

- Pinewood Derby Feb2020

- Ski Trip Feb 2020

- Merit Badges at Cradle of Aviation Museum

- Cabin Sleepover March 2020

- Klondike Derby - Jan 2020

- Ski Trip Jan 2020

- First Aid Merit Badge - 2019

- Homeless Solutions_Oct2019

- Webelos Woods - Fall 2019

- AT Hike - Fall 2019

- Deep Sea Fishing - Nov 2019

- Pumpkin Sale Fall 2020

- Shooting Trip - Fall 2019

- 2019 Labor Day Parade

- 2019 Pastime Club Carnival

- July 4 Parade - 2019

- Jersey Jam - 2019

- Sabattis Merit Badges 2019

- Gettysburg Camping April 2019

- 2019 Memorial Day Flag Ceremony

- AT Hike Spring 2019

- Canoe Trip - May 2019

- Bike Trip May 2019

- Sabattis 2019

- 2018 West Point Camporee

- Scuba Discovery Mar 2019

- Homeless Solutions_Sept2019

- Black River Day Hike

- Pinewood Derby Feb2019

- Rock Climbing - Jan 2019

- Ski Trip Jan 25-27 2019

- Caving Trip / Geocaching Merit Badge - Fall 2018

- Pack 133 Presentation

- Trevor Zaybekian Eagle Project

- Webelos Woods - Fall 2018

- Pumpkin Sale Fall 2018

- Swiss Alps - High Adventure 2019

- AT Hike - Fall 2018

- Shooting Trip - Fall 2018

- Deep Sea Fishing - Oct. 7, 2018

- 2018 Labor Day Parade

- 2018 Pastime Club Carnival Sign-up

- 2018 CO Trail HA

- Model Rockets with Pack 133 - June 2018

- Sabattis 2018

- Sabattis Merit Badges 2018

- Whitewater Rafting June 2018

- Bike Trip June 2018

- AT Hike - Spring 2018

- Canoe Trip - May 2018

- Go Kart Trip April 2018

- Cabin Sleepover March 2015

- AOL Crossover Ceremony - March 2018

- High Adventure Sea Base FL - Summer 2018

- Pinewood Derby Feb2018

- Klondike Derby - Jan 2018

- Ski Trip - Jan 2018

- Rock Climbing - Dec 2017

- 2018 High Adventure Interest

- Homeless Solutions_Jan2019

- Webelos Woods - Fall 2017

- Pumpkin Sale Fall 2017

- AT Hike - Fall 2017

- Sailing at Mystic Seaport

- Whitewater Rafting June 2017

- AT Hike - Spring 2017

- Pastime Club Carnival Sign-up

- Gettysburg Camping 2017

- Bike Trip April 2017

- Annapolis April 2017

- Sabattis 2017

- Cabin Sleepover March 2017

- 2017 Day Hike

- Scuba Discovery Feb 2017

- Pack 133 Blue and Gold - March 25, 2017

- AOL Ceremony March 2017

- Philmont 2018 Interest Survey

- Pacific NW High Adventure - Summer 2017

- Ski Trip - Jan 2017

- Shooting Trip - Fall 2016

- Rock Climbing - Fall 2016

- Webelos Woods - Fall 2016

- NJ State Police Camporee - May 2017

- Deep Sea Fishing - Oct. 8, 2017

- Deep Sea Fishing - Sept. 25, 2016

- AT Hike - Fall 2016

- Labor Day Parade

- Whitewater Rafting June 2016

- Sabattis 2016

- AT Hike - Spring 2016

- Caving Trip Fall 2016

- Canoe Trip - May 2016

- Bike Trip - April 2016

- Cabin Sleepover April 2016

- Jamboree 2017 Interest

- 2016 Day Hike

- Scuba Discovery Feb2016

- Pinewood Derby Jan2016

- Klondike Derby - Jan 2016

- Go Kart Trip Mar 2016

- Ski Trip - Feb 2016

- Ski Trip - Jan 2016

- Rock Climbing - Fall 2015

- Shooting Trip - Fall 2015

- Wilderness Survival Campout - Fall 2015

- Pumpkin Sale - Fall 2015

- AT Hike - Fall 2015

- Deep Sea Fishing - Sept. 26, 2015

- Eagle Project for Matt Fabrizio

- Whitewater Rafting June 2015

- AT Hike - Spring 2015

- Lewis Morris Campout - May 2015

- Sabattis 2015

- Bike Trip - April 2015

- Philmont 2016 Interest Survey

- Pack 133 Crossover February 2015

- Philmont 2016 Sign-up

- Go Kart Trip Feb 2015

- Klondike Derby - Jan 2015

- Ski Trip - Jan 2015

- AT Hike - Fall 2014

- Dutch Springs Scuba Certification - August 2014

- AT Hike - Spring 2013

- High Adventure Sea Base FL - Summer 2015

- High Adventure NH - Summer 2014

- Scuba Certification - Winter 2014

- Scuba - Nov 2013

- Whitewater Rafting June 2019

- Kevin Jamer's Eagle Project

- Matt Cantale Eagle COH_March 2, 2019

- Pat Martin's Eagle Project

- Swiss Trip Carpool 2019

- Sam Dickens Eagle Project

- Ethan Ryan Eagle Project

- JBWS Letter

- SPL Election

- Matt Messina's Eagle Project

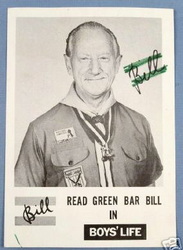

"Green Bar" Bill Hillcourt

William Hillcourt (August 6, 1900 – November 9, 1992), popularly known within the Scouting movement as "Green Bar Bill" and "Scoutmaster to the World", was an influential leader in the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) organization for much of the twentieth century, acclaimed as "the foremost influence on development of the Boy Scouting program".

Hillcourt is especially noted as a writer and teacher in the areas of woodcraft, troop and patrol structure, and training. He was a prolific writer; his works include three editions of the BSA's widely-circulated official Boy Scout Handbook, with over 12.6 million copies printed. Hillcourt developed and promoted the American adaptation of the Wood Badge program, the premier adult leader training program of scouting. Hillcourt was born in Denmark but moved to the United States as a young adult where he worked for the BSA. From his start in Danish Scouting in 1910 though his death in 1992, he was continuously active in Scouting. He traveled all over the world teaching and training both scouts and scout leaders (scouters), earning many of Scouting's highest honors. His legacy and influence can still be seen today in the BSA program and in Scouting training manuals and methods for both youth and adults.

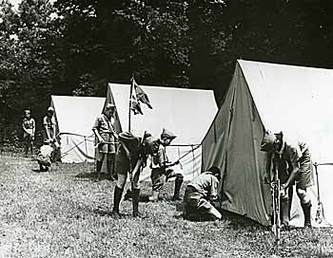

Hilllcourt founded Troop 1 in 1935 and it was directly chartered to the National Council of the BSA. As the Troop 1's Scoutmaster for the next 16 years, William Hillcourt developed the "boy-led" system of Scouting used across the country. The boy-led system of Scouting, developed in Mendham, New Jersey at Troop 1, remains a core principal at the Troop 1 to this day. It is a significant part of what makes the Troop 1 experience so effective in developing tomorrow's leaders.

To learn more about William Hillcourt read his autobiographical essay Life of a Serendipist reproduced below.

William Hillcourt (August 6, 1900 – November 9, 1992), popularly known within the Scouting movement as "Green Bar Bill" and "Scoutmaster to the World", was an influential leader in the Boy Scouts of America (BSA) organization for much of the twentieth century, acclaimed as "the foremost influence on development of the Boy Scouting program".

Hillcourt is especially noted as a writer and teacher in the areas of woodcraft, troop and patrol structure, and training. He was a prolific writer; his works include three editions of the BSA's widely-circulated official Boy Scout Handbook, with over 12.6 million copies printed. Hillcourt developed and promoted the American adaptation of the Wood Badge program, the premier adult leader training program of scouting. Hillcourt was born in Denmark but moved to the United States as a young adult where he worked for the BSA. From his start in Danish Scouting in 1910 though his death in 1992, he was continuously active in Scouting. He traveled all over the world teaching and training both scouts and scout leaders (scouters), earning many of Scouting's highest honors. His legacy and influence can still be seen today in the BSA program and in Scouting training manuals and methods for both youth and adults.

Hilllcourt founded Troop 1 in 1935 and it was directly chartered to the National Council of the BSA. As the Troop 1's Scoutmaster for the next 16 years, William Hillcourt developed the "boy-led" system of Scouting used across the country. The boy-led system of Scouting, developed in Mendham, New Jersey at Troop 1, remains a core principal at the Troop 1 to this day. It is a significant part of what makes the Troop 1 experience so effective in developing tomorrow's leaders.

To learn more about William Hillcourt read his autobiographical essay Life of a Serendipist reproduced below.

"During the sixteen years of my Scoutmastership, Troop 1, Mendham, New Jersey, was the most photographed Scout troop in the world."

The Life of a Serendipitist

By William Hillcourt

Did you ever hear the story of the King of Serendip? He had three sons. He

was proud of them and saw to it that they had the very best upbringing. He

brought in the finest swordsmen and athletes of his kingdom to coach them in all

the fitness skills of a true knight. He had the wisest men of the country teach

them about the world and its wonders. He himself taught them kingship: how to

rule with compassion and fairness.

He loved his three sons equally well. But as he grew old, he wondered which

of them would make the best king when his own days were up. He decided to put

them to the test: He sent them out into the world with one year to find a very

special treasure. When the year was up, they returned.

All three had failed! Not one of them had found the treasure he had been sent

out to find. BUT-each of them had found a treasure far more precious than any

their father could have imagined!

Out of this story of the King of Serendip have come two words for the English

language: serendipity, a gift for finding valuable things not sought for, and

serendipitist, the person who does the finding.

Columbus, the greatest serendipitist of all time, became one at the age of

41. I became one at 25. The treasure Columbus sought was the fulfillment of his

dream of finding India by sailing west. Mine was the fulfillment of a similar

dream: of circling the globe before settling down in my native Denmark for the

rest of my life.

Columbus failed in his quest. He did not find the route to India. He found

something far superior: a new world. I failed in mine-for the time being. But I,

too, found something far better than what I sought. I found a different country

to treasure and serve, a girl to love and cherish, a challenging career and a

lifework in Scouting.

It took some doing. It took timing, special skills, willingness to take a

chance and the ability to recognize treasure when I saw it, plus some

extraordinary coincidences. As to timing: I was born at exactly the right time

for Scouting, in 1900, the year when a British officer by the name of Robert

Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell became the greatest military hero in the war the

British Empire was fighting in South Africa.

I was 10 at the right time for becoming a Scout in Denmark: Baden-Powell’s

Scouting for Boys had just been translated into Danish. I got it for a Christmas

gift. It told me how to become a Scout. I became one in January 1911.

I was at the right age also and had reached the right advancement-the Danish

equivalent of Eagle-when my troop picked me to represent it at the first World

Jamboree inLondonin 1920. I celebrated my birthday that year by joining 5,000

other Scouts in proclaiming Baden-Powell Chief Scout of the World.

And my timing was right when, at 25, I set out to see the world, fit and

prepared with the kind of know-how I would need to get along.

But let me get back to my beginnings.

I was born on August 6, 1900, in Aarhus,Denmark, the third son of a prosperous

building contractor. My childhood years were carefree ones. My teen-age years

were rough. My father nearly went bankrupt in an economic depression of 1909. He

kept the family afloat building stations for the expanding Danish railroad. We

moved from place to place wherever his work took him. My Scouting became Lone

Scouting: Troops were few and far apart in those early days of Danish Scouting.

When we finally returned to my home town, my Scout life really took off. I

became a patrol leader and senior patrol leader in Aarhus Troop 3 under an

extraordinary Scoutmaster, Jorgen Boje.

By then I had to think of my future. My main hobbies as a boy had been

chemistry and botany. They added up to pharmacy. For my early training, I became

a “disciple” in the 400-year-old pharmacy of my home town. When my disciple

years were over, I went to Copenhagento finish my studies at the Pharmaceutical College.

I had hardly arrived before I was invited to become the Scoutmaster of Copenhagen’s

most famous troop, Vedel’s Own. I accepted.

I had another childhood hobby to satisfy: writing. In whatever time I had

left from studying and of the Danish Boy Scouts, got out a Scout handbook and

wrote a boys’ book based on the experience of my own patrol camping on a desert

island in Denmark’s largest lake. It wasn’t a runaway best seller, but it had a

respectable sale for a first novel by a 23-year old.

Danish Scouting was a stir in those days. The Danish team at the lst World

jamboree in London had won the world championship in Scouting. Because of that,

the 2nd World Jamboree was coming to Denmark. I made up my mind that my

whole Copenhagen troop would take part in it. It did.

At the same time I made up my mind about my own future. I had become a

full-fledged pharmacist in May 1924. One week after, I walked into the office of

one of the largest Copenhagen newspapers and offered my services as its jamboree

correspondent. “I know all about jamborees,” I told the editor. I had been at

the only one ever held. “And I can write.” I had two books to show him. He took

me on. And I left pharmacy forever.

My reporting must have been satisfactory. After the jamboree, the editor made

me the managing editor of the paper’s Sunday magazine. I could look forward to a

good solid newspaper career.

But I had become a restless dreamer. The two world jamborees had stirred my

blood. I had met people from around the world. I wanted to meet them on their

home grounds. I arranged with my newspaper to be its roaming reporter on a trip

around the world. I took off in September 1925, covered London and

southern England, then settled down for a month in Liverpool to write another boys’

book. It paid my boat fare for New York, where I landed in February 1926. There I

spent the spring writing articles about its teeming life.

From time to time I visited the national office of the Boy Scouts to pick up

my mail from Denmarkand to see a friend, Bill Wessel. He had been the Scoutmaster

of the American troop that won the world championship in Scouting at the

jamboree in Denmark. He arranged for me to spend the summer at the camp of the

New York Boy Scouts.

It was here that I became an Indian “expert.” Besides taking part in the

camp’s main activities, I spent much of my time in the sub camp run by Julian

Salomon who later wrote the book Indian Crafts and Indian Lore. He was to have

staged four Indian dances for the large pageant that was to close the camp

season but was called home because of illness in the family. The pageant

director was frantic. Julian calmed him. “Use the Danish Scout,” he said, “he

knows the dances.” So I was put to work teaching half-a hundred Brooklyn Scouts

four Indian dances. The pageant was a success.

The Danish Chief Scout had asked me to find out how the sales of Scout

uniforms and equipment were handled in other countries - in Denmark they had been in

private hands from the start. To learn, I took a job with the BSA Supply Service.

On a cold December day I was checking in a shipment of World War I surplus

army signal flag poles in front of the warehouse when one of the heavy boxes

tumbled over, knocked me down and broke my right leg. An ambulance rushed me to

the hospital. The bones were set and a plaster cast applied. I was out on the

street on crutches three days later. I wasn’t particularly perturbed. “The Lord

will provide,” I figured. He did.

A week after my accident I hobbled into the national office on my crutches to

pick up my mail. I was walking to the elevator when an astonishing coincidence

changed my life completely. Someone else was on his way to the same elevator:

James E. West, the dynamic Chief Scout Executive of the Boy Scouts of America.

He knew of my accident. He stopped to greet me, then said, “Well, my young man,

what do you think of American Scouting?” The elevator came. We went down

together, chatting.

His words may have been just a casual remark. But I took them seriously. I

wrote an 18-page report and sent it to him. It was complimentary in spots,

critical in others. But for each criticism I offered a suggestion for remedying

the situation.

Within a week, he had me in his office. “While I don’t agree with everything

in your report, I am interested in what you say about the Boy Scouts of America

not using the patrol method effectively. You suggest that we should have a

Handbook for Patrol Leaders. What should it contain?”

I told him what I had in mind.

“Would you be interested in writing it?” he asked.

“I should like to,” I said, “but my English isn’t that good.”

“For any person in this world who has an idea,” he told me, you can get a

hundred to put it in final shape. So why not try?”

And that’s how I became a member of the national staff of the BSA.

My English in those days was the English of a 13-14-year-old American school

boy, exactly the age of the boy leader for whom the book was intended. My

manuscript was hardly touched in editing. I received the first copy of my first

book in English the day I arrived at Arrowe Park, Birkenhead, England, for the

opening of the 3rd World jamboree, July 31, 1929.

That fall the bottom fell out of the American economy with the stock market

crash of October 29. The United Statessank into the deepest depression in its

history. All phases of American life were affected, including magazine

publishing. James E. West was determined that Boys Life, the Boy Scout

magazine, should survive. But money was needed. He applied for a Rockefeller

Foundation loan. The foundation studied the magazines contents. It came to the

conclusion that Boys Life was not sufficiently different from the other

boys’ magazines to warrant the loan. But it hinted that it might reconsider if

more Scouting material were added.

I suddenly found myself an assistant editor of Boys’ Life responsible for

editing its Scouting sections and writing a monthly feature of MY own. What

should it be? I decided on a page of hints for patrol leaders. To make it more

exciting, it should be written by a mysterious person. By what name? The patrol

leader’s badge in those days was a square of cloth with two green bars

embroidered on it. I took those bars, added my nickname and became Green Bar

Bill in the October 1932 issue of Boys Life.

The following spring I made one of the most important decisions of my life. I

had found the girl of my dreams, Grace Brown, the Chief Scout Executive’s

personal secretary. As a teenager, she had vowed never to marry a foreigner,

never to marry a blond, not to get married in June. But when a blond foreigner

said to her, “The boat leaves for Europe on June 3, will you marry me?” She didn’t

say “No” and she didn’t say “Yes’-she said, “Of course!” She knew that all Danes

spend most of their lives riding bicycles. She decided that our honeymoon trip

through Denmark, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria and into Hungary for the 4th World

Jamboree should be by bike. We had an adventurous journey of exactly 100

days.

Back home again, we settled into a New York City apartment-but not for

long.

The Schiff Scout Reservation, a beautiful 480-acre estate in the rolling

hills of New Jersey, had been dedicated in 1933 as a training center for the Boy

Scouts of America. Green Bar Bill had a dream that he conveyed to the Chief

Scout Executive: “If Green Bar Bill is to go on urging patrols to a vigorous

life in the outdoors, he should live in the outdoors he is writing about. He

should live on the Schiff Scout Reservation.” West agreed. Green Bar Bill and

his mate moved into their new home - a remodeled sheep barn in September 1934.

The twenty years that followed became the most productive of my whole

life.

My first major assignment at Schiff was the writing of a new Handbook for

Scoutmasters. I had been a Scoutmaster in Denmark but knew nothing about

Scoutmastering American boys. To write the book, I had to know. I gathered the

boys of the nearby Mendham village into a troop and took on the job of

Scoutmaster. During the sixteen years of my Scoutmastership, Troop 1, Mendham, New

Jersey, was the most photographed Scout troop in the world.

The earliest photographs were used to illustrate the Scoutmaster handbook.

But when Life magazine came out in 1936 with a new kind of news

reporting-photojournalism, combining photographs and captions-I figured that

Scoutcraft could be learned the same way. I got the camera equipment I needed, a

studio, a darkroom and a helper. With the Mendham Scouts as enthusiastic models,

we turned out Boys Life photo features on hiking and camping, cooking

and pioneering, swimming and Indian dancing, and many other subjects.

The hundreds, yes, thousands of pictures that were taken came in handy for my

next brain storm: a handbook on Scouting illustrated entirely with photographs.

It became our first Scout Field Book.

But, possibly, the most important thing to come out of the years we lived at

Schiff was the relationship we established with the Chief Scout of the World and

his wife, Lady Baden-Powell.

It began on a visit by the Baden-Powells to Schiff in 1935, when Lady B-P, by

the coincidence of being with “the right people” at the right time came for

breakfast with the Hillcourts and asked her husband to join us afterwards in our

cottage. The relationship was greatly strengthened two years later during and

after the 5th World Jamboree inHolland. The Baden-Powell’s adopted Grace while I

was in camp and had us for house guests at “Pax Hill,” their home inEngland,

afterwards. This close relationship specifically with Lady Baden-Powell after

B-P’s death in 1941had some important outcomes: She granted me permission to

edit Baden-Powell’s Scouting for Boys into the World Brotherhood Edition that

helped reestablish Scouting in devastated countries around the world after World

War II. She helped me with the research for my biography about the founder of

Scouting,BadenPowell-The Two Lives of a Hero, by turning over to me all her

husband’s letters, diaries and sketchbooks. She later presented all these

valuable documents to the Boy Scouts of America.

In 1954, the national office of the Boy Scouts of America was moved fromNew

York City to its own building inNorth Brunswick,New Jersey. In addition to my

regular work, I was now assigned the most important task of my whole Scouting

career the writing of a new Handbook for Boys to celebrate the forthcoming

Golden Jubilee of the Boy Scouts of America. This would involve intensive work

in the national office. And so, the Hillcourts left the Schiff Scout Reservation

after twenty years and moved into a garden apartment within walking distance of

the office.

The new handbook, for the first time with color illustrations and written by

a single author, and with the new title of Boy Scout Handbook, was ready for the

50th anniversary festivities in February 1960. So was another book of

celebration, The Golden Anniversary Book of Scouting, with text by Bill

Hillcourt telling the 50-year history of Scouting inAmerica.

The day for my retirement from the national staff of the Boy Scouts of

America arrived August 1, 1965. Grace and I, in 1971, celebrated it by taking

off on the trip around the world I had failed to complete at 23. We made it

coincide with yet another jamboree, the 13th, inJapan. It was Grace’s sixth and

last before she died in 1973. It was my ninth. I finally managed to attend 13

world jamborees out of 15 and all the national Jamborees.

Except for traveling, I had expected a fairly tranquil retirement. But

something else was “in the works” that would change my plans again.

A new handbook for Boy Scouts was needed, one that would tell about the

romance and excitement of Scouting. I came out of retirement and gave the Boy

Scouts of America an offer they couldn’t refuse: “I will give you a year of my

life free, gratis, without pay, to write a new Boy Scout Handbook.” My offer was

accepted. I started the book October 25, 1977. I finished it October 25, 1978.

It came out on schedule, February 8, 1979. Today, three million copies are in

print.

After that Boy Scout Handbook came out, I traveled around the country and

spoke to Scouters by the thousands at council dinners and conferences. I have

met Boy Scouts, Cub Scouts and Explorers by the tens of thousands at large

council shows and camporees, at Diamond Jubilee celebrations and at the National

Jamboree.

You may even be one of those Scouts. Did I sign your book? Were you one of

the Scouts who asked me if he might shake my hand? Did you possibly press a

troop badge or a council patch into my hand? Wherever we may have been together

we must both have felt the same vibrant spirit all around us: a great pride in

the past of our movement and faith in its future.